This post has little to do with gender and everything to do with sisterhood.

In less than two years I’ve lost four important women in my life, two blood sisters and two chosen sisters, and the grief is almost unbearable. I’m swallowed up by the hole that these women left behind, and I go about my day in an almost zombie-like resignation. My world shrinks as I gain weight because I am eating my feelings (or is it my newly diagnosed hypothyroid? The same hypothyroid disease my two dead sisters contended with while alive? The same hypothyroid problem two of my nieces contend with now?).

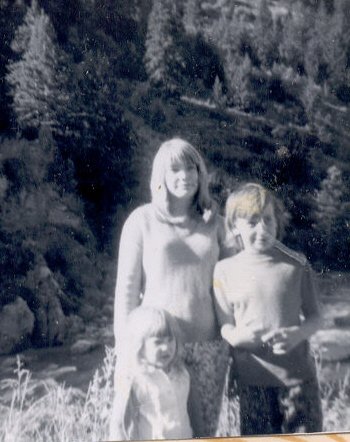

First, I lost my sister Nancy to Covid-19. No. First, I lost my sister Nancy to dementia, and then to Covid-19. Wait. No. First, I lost my sister Nancy to Fox News and then to dementia and then to Covid-19. I lost my sister Nancy, the woman who bragged about raising me, who taught me how to sing, who showed me the joy of flirtation, and the thrill of drama. I lost my sister Nancy, with whom I had little in common with, except DNA, and a sense of humor, and a sense of wonder, and a belief in ghosts and hauntings.

The day after Nancy died, my goddaughter called to tell me it was time. Her mother had been fighting pancreatic cancer but was losing. My goddaughter called to tell me to come say goodbye, now, immediately, don’t wait, and my lovely trans-wife and I rushed an hour away and to the side of my friend, who was eaten from the inside out from cancer. My friend, Michelle, was a living corpse, her face sunken like the photos we see of people in World War II concentration camps. Pancreatic cancer is a horrible thing, a nightmare, and it ate up my lovely, gorgeous, vivacious friend Michelle. She died 45 minutes after Natalie and I left her house. I felt guilty for not having spent more time with her, for not having told her repeatedly how much I loved her. I felt guilty for assuming too much. For thinking her stomach pains were stress, and her fear that something was wrong was perimenopause. I felt guilty, but relieved I was able to tell her I loved her, that I had always loved her, that I never stopped loving her, and that I promised to love her daughter just as loyally and as long and longer.

Time passed and other people died, too. Lots and lots of people died from Covid-19. Every night the news reported the losses. So much death. So many families grieving.

My friend, Walter, from high school who lived in St. Louis, too, died. He had once expressed to me the thought that I often thought but never said out loud, “We survived Raytown, Max,” he had said. “We got out of there!” Walter had a perpetual smile and positivity about him, and it is this positivity that probably helped him survive. He survived Raytown but no amount of goodwill and good nature can survive cancer.

Natalie’s Aunt Sandy survived cancer longer than anyone expected, but she, too, died during this time. We were able to attend her graveside funeral, because Covid-19 is less scary when we’re all outside. It was windy and cold and I was shaking from loss and from the wind. Aunt Sandy was a teacher, a bird lover, a friend to hundreds of hummingbirds who visited her feeders. Who feeds her hummingbirds now? Does her husband, Don, remember to?

My childhood friend, Tammy, lost her mother to dementia. I talked to Tammy quite a bit while her mom was sick, while Tammy took care of her mom, while Tammy put her own life on hold to take care of her mom. After her mom passed, I sent Tammy chocolates and asked her to come visit. “I’ll pay for your train ticket,” I said. “Leave Raytown for awhile. Come see me!” I pleaded. And she promised she would, but I wondered. Her grief was wider than the miles between us. She didn’t have a memorial for her mother, because she couldn’t afford it, and she was afraid no one would come.

Nancy’s memorial service was through Zoom. There were no heartfelt hugs, no shared tissues, no pushing back a family member’s hair wet with tears. No softness. Just tiny boxes filled with grieving faces blinking on the computer screen.

Eventually, I started to heal. We had vaccines! We had hope! We left our homes and entered into each other’s homes and restaurants and theaters. We took off our masks. We smiled at each other. I finally felt the heart-to-heart warmth of hugs from people I love. I invited Tammy again and again. “Please come visit,” I said. “We’ll see, kiddo,” she said. And finally I left it at that.

Not long ago, a day, a week, a month ago, Tammy’s brother called me sobbing. Tammy had passed away in her sleep. My childhood friend, another of my chosen sisters gone. Suddenly, without warning. No goodbyes. Just gone. Gone. Her daughter suspected a heart attack. The autopsy confirmed her daughter’s suspicions. Her two daughters held a memorial service for her in Kansas City, but the Omicron variant kept me away. I watched the livestream on my phone and sobbed, alone.

Meanwhile, I transferred campuses, took on the unglamorous and uncompensated role of department chair, because I am resigned to a life of work and death. I am resigned to this dystopian hellscape we now find ourselves in. Just when we think it can’t get any worse, it does, and I am resigned to settling in to the safety of work. At work, I have some modicum of control. At work, I don’t have to love anyone. (Even though, I do. I love my students more than they realize. I love my colleagues. I love the staff. I love the idea of a community college, and I love that I can talk and talk and talk about a subject I love to people who want [or are sort of forced] to hear).

As a new chairperson, I wanted to make a good impression. None of these people know me. They know nothing about me. They don’t know I am married to a transwoman. They don’t know I wrote a book of erotica. They don’t know I was gang raped when I was a kid. They don’t know how passionate I am about teaching and the arts and literature and community. They don’t know that I will love them fiercely. They don’t know what I have in store for them. So, when I chaired my first department meeting with them, I wanted to make a good impression.

Making impressions via academic Zoom (a.k.a. Microsoft Teams) is not easy or intuitive, and if what happened had happened in a face-to-face meeting, I may have reacted differently. But we were all in our little computer screen boxes sizing each other up while discussing the business at hand when I received a text from my niece that my sister Glenda had passed away. Then my brother called and without blinking I silenced my phone. All the while, I remained stoic, kept smiling at my new colleagues, continued on with the meeting, while deep inside I simply wanted to scream scream scream scream scream scream scream. I didn’t say a word to any of them about what was happening to my family at that moment. When the meeting was over, I asked the two secretaries to stick around, not log off, and it was to them that I bared my ugly news: my sister had passed away. And while I was telling them this, I looked out my home office window and saw the ambulance at my elderly neighbor’s home. I watched as they transported my neighbor’s body from the house to the vehicle. I realized my neighbor had died, too.

The very air is shrouded.

Here’s the thing about sisterhood: It doesn’t die. No matter what.

My sister Glenda and I had been estranged for over 20 years, so when I initially found out she had stage 4 lung cancer I didn’t call her. Thanks to the gentle coaxing and interference of my niece and my brother, I extended an olive branch to Glenda and we finally spoke briefly on the phone two days before she died. I could hear death in her voice. I knew it wouldn’t be long before she passed. I knew Glenda and I didn’t have time to patch things up, really talk about what had happened between us. We didn’t have time. The only thing we could do was confess our sisterly love for each other and feel satisfied that love remains no matter how hard the feelings, the disagreements, or the distance in between.

The only thing we can do is confess our sisterly love for each other and feel satisfied that love remains no matter how hard the feelings, the disagreements, or the distance in between.

My heart breaks for you, Max. Thank you for sharing so eloquently about your pain and loss. Sometimes it feels like the world is being tossed around in a giant drum dryer.

I know you will continue to find bits of joy in your life. Loving other people is a gift you have.

LikeLike

Thank you Max for using your grief to remind me to speak love as often as possible. I love you

LikeLike